Introduction:

Non-surgical facial rejuvenation in men has increased in popularity. The increasing number of products, indications for treatment, and impact of social media have popularized facial rejuvenation for men. However, male aesthetics goals differ dramatically from their female peers, and while the aging process of males and females share many features, the differences must be highlighted. In general, male patients typically want to address the aging/“tired” appearance or masculinize various aspects of the facial contour but tend to fear looking “overdone”1. Just as with any aesthetic treatment, the unique anatomy of each patient must be discussed in detail and treatment goals established early on.

Aging Process:

The aging face is characterized by three main processes: 1) loss of skin elasticity and gravitational effects 2) loss of bony skeletal support 3) facial volume atrophy. There is considerable overlap in this process as volume loss results in redistribution of tissue over the mandibular angle, for example, and loss of distinct mandibular borders. This holds true for both male and female patients. While this simplistic model does not account for all the complexities involved with the aging face, these three components help drive our current treatment strategies at rejuvenation both surgically and non-surgically.

Dermal Fillers:

Dermal fillers have evolved greatly since the introduction of Restylane in 2005. Fillers are defined by their rheologic properties such as HA concentration, particle size, G’, flexibility, and hydrophilicity to name a few. These parameters predict behavior in vivo and guide decision making when choosing a product for a specific anatomic area. As discussed previously, hyaluronic acid fillers correct one part of the aging process: volume loss. Choice of product is only one component of the aesthetic treatment. Achieving good aesthetic outcomes rests on both good pre-operative assessment and execution of appropriate injection techniques for the specific anatomic area.

Male Aging Process:

Skin:

The epidermis and dermis of the male skin is thicker, more elastic, and more vascular than female skin. This increase in vascularity is due to more coarse facial hair than female patients. Over time the skin becomes thinner and loses collagen, elastin, and HA. Environmental factors speed the aging process (UV radiation, smoking, etc) and men typically engage is lifestyle habits that increase the speed of skin aging. 2

Bone:

Changes in the bony facial skeleton contribute to the signs of aging in both males and females. Loss of bone in the mandible, midface, and forehead contribute to a loss of support for the skin and soft tissues of the face and neck. Common features include blunting of the mandibular angle, increase in the pyriform aperature, midfacial bone loss, widening of the orbital aperture, and deepening of the nasolabial folds2, 3. Men begin life with a higher bone mass than women and lose less over time. In men, changes in the forehead lead to a more pronounced supraorbital rim and loss of mandibular angle definition. The latter being one of the more characteristic male features.

Fat:

Our understanding of facial volume loss has greatly increased with the landmark articles by Rohrich and Pessa beginning in 2007. Understanding and treating volume loss had been the missing link for optimal aesthetic rejuvenation that previously focused mostly on “lifting”, pulling, and directed filler towards lines. Facial fat is found in two compartments: deep and superficial. One helpful way to differentiate these is by grasping and lifting the skin and fat on your own face, with superficial fat being graspable. Depletion and loss of even distribution of these fat pads leads to predictable age-related changes in the male and female face. These include temporal hollowing, midface ptosis, and perioral hollowing. The end result of these processes leads to familiar signs of aging including: loss of cheek projection, brow ptosis, nasolabial folds, jowls, and marionette lines4. Males begin with less subcutaneous adipose tissue and thus end with deeper wrinkles and lines than in women5.

Approach to the Upper Third:

Males typically have more severe facial rhytids than women except in the perioral area. Subcutaneous loss of adipose tissue combined with thicken skin and stronger musculature lead to deeper and more severe wrinkles5. Deeper lines and volume loss cause men to appear older than women at similar ages. In the upper face, neuromodulators can be used to soften these lines and wrinkles to great effect. In fact, botulinum toxin is the single most common cosmetic procedure performed in men. (ASAPS survey 2015). Given the stronger muscles found in men, higher dosages of botulinum toxin are typically required. In men, the eyebrow should be kept low and straight. No more than a 5-degree elevation at the tail of the eyebrow should be tolerated to avoid feminization. Therefore, it is important to inject the lateral aspects of the frontalis muscle. This will help prevent arching of the temporal brow which is a distinctly feminine look6. Additionally, men have a lower eyebrow position at rest. Therefore, care must be taken in the total dosage as well as injecting low along the frontalis muscle to avoid brow ptosis. Due to androgenic alopecia the hairline in men is typically much higher in women. Compensatory movement and lines may develop high into the hairline in men which can be avoided by careful placement of botulinum toxin high up into the frontalis.

Approach to the Midface:

Male and female cheeks differ in their contour and aesthetic. Cheek augmentation using dermal fillers is typically taught using injection techniques designed for the female patient. When replicated in men, this can overly feminize the cheek. Key differences must be highlighted between the point of maximum cheek projection in a male and female face and will be discussed here.

Female Cheek:

The apex of the female cheek is found at the intersection point of a line from lateral orbital rim to the oral commissure and a line from the alar groove to the upper tragus. One can use the golden ratio (1:1.6) to confirm placement of this point where the intercanthal distance is 1 and the distance of the medial canthus to the maximal cheek projection point is 1.6. This point corresponds to the apex of the cheek in an oval shaped cheek mound which can be augmented with dermal filler7. In males, this point is found differently.

The authors prefer a multi-planar technique for cheek augmentation with three pre-periosteal boluses of dermal filler (approximately 0.1cc) along the zygomatic arch with a 27G needle. These boluses start at the cheek apex and proceed laterally. Next, subcutaneous placement of filler in the deep fat compartments is performed using 25G cannula using a fanning method. It is important to evaluate both the anterior/medial cheek as well as the sub-zygomatic cheek to determine which areas require augmentation. The aesthetic goal in a female is to create an ovoid, angular cheek mound with an eccentric cheek apex along the zygomatic arch. This restores the natural ogee curve on three-quarter view when done properly.

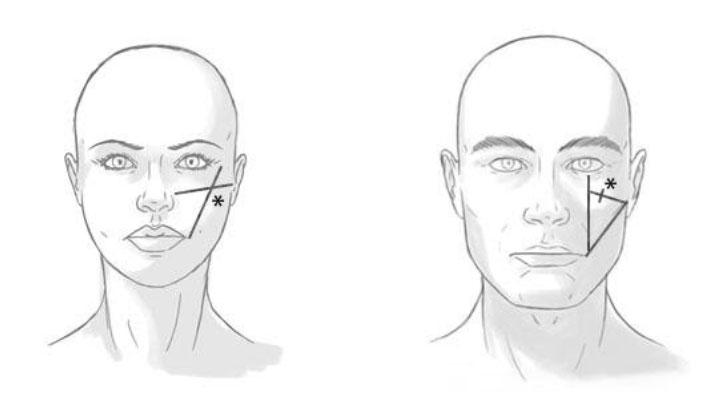

Left: Female cheek apex found by drawing a line from the oral commissure to the lateral orbital rim and a second line from the upper tragus to the alar groove. The point of intersection marks the cheek apex (asterisk)

Right: Male cheek apex found by drawing a line from the lower tragus to the oral commissure and a second line from the lateral limbus to the oral commissure. Bisecting these two lines completes the triangle. 1/3rd the distance of this line marks the cheek apex (asterisk)

Male Cheek:

To find the male cheek apex one creates two lines: one from the lower tragus to the oral commissure, and one from the lateral limbus straight down to the oral commissure. This creates two limbs of a triangle that can be closed by a third line connecting the two. The male cheek apex point is 1/3rd the distance of this bisected line from the lower eyelid. This point can be confirmed using golden ratio calipers with the intercanthal as the distance 1 equaling the length from the lateral limbus to the cheek apex point. Additionally, the length of the bisected line should equal 1.6. The male cheek apex point sits lower and more medial than in women. This ensures dermal filler augmentation does not raise and/or lateralize the cheeks which results in a distinctly feminine look. Volumizing the cheek at this point ensures masculine features are kept and enhanced.

The authors again prefer a multiplanar technique for cheek augmentation however with only one pre-periosteal bolus of dermal filler at the cheek apex point (0.1-0.2cc). Next, subcutaneous placement of filler in the deep fat compartments may occur along the medial aspect of the cheek. Care must be taken to avoid placement of filler laterally and high along the zygomatic arch as this will produce a distinctly feminine cheek.

Tear Trough:

The male face has a flatter and medial cheek which can lead to a more pronounced tear trough deformity. This gives an aged and tired appearance and is a common complaint among men seeking aesthetic treatments. The pathophysiology of this deformity is similar to women and involves the interplay between the orbital fat and septum superiorly, the tight orbicularis retaining ligament (ORL) which creates the “line” of the tear trough deformity, and the medial cheek inferiorly. As we age the orbital fat can begin to herniate through the septum creating puffiness under the eyes. The overlying skin and muscle can also become lax over time. Typically, men and women lose volume in the medial cheek which exacerbates the tear trough deformity with fat herniation superior to the ORL and volume loss below. It is important to mention that proper patient selection is crucial in successful outcomes in non-surgical rejuvenation of the tear trough using dermal filler. Patients must not have large pseudo herniated orbital fat bags and have good skin and muscle quality for optimal results. Proper product selection and slow correction over multiple visits are also vital.

Approach to the Lower Face:

The approach to the lower face involves two primary considerations 1) enhancement of an underdeveloped or under projected mandible and chin, and / or 2) restoration of a distinct border following volume-loss and tissue migration, bony resorption (3) at the angle and menton, and the contributions of soft-tissue laxity at the pre-jowl sulcus8. A distinct and projected angle, smooth transition between the chin and mandibular body, and assessment of contour relative to the midface provides a framework for optimal aesthetic outcomes9.

Prior to jawline enhancement for the young male patient, the authors assess the mandibular angle projection (i.e., width) with respect to the midface. In our opinion the classic “masculine” appearance highlights lateral cheek projection with light reflex at the border of the zygomatic arch, submalar shadow, proportionate jawline projection and width, and submandibular shadowing.

The authors prefer calcium-hydroxylapatite (CaHA) (due to less hydrophilicity and ability to maintain structural integrity) using a multi-planar technique using both needle and cannula. Chin projection and shape is initially evaluated with respect to the lip, and augmentation involves pre-periosteal injections at the menton using a 27” 1.25” needle. This is followed by subcutaneous cannula injection along the body of the mandible to minimize isolated central projection, and to blend a projected chin with the body.

The angle of the mandible is addressed through both bolus injections in the pre-periosteal plane directly at the angle with a 1.25” needle of up to 0.3ml, followed by subcutaneous injections towards the mandibular angle parallel to the body, and again paralleling the ramus. The authors suggest pushing past the eye of the cannula does not open at the tip of the cannula and tunneling slightly under the border of the mandible to prevent unnatural volume above the body during animation. The body is injected last with a cannula in the subcutaneous plane only if further projection is warranted, however the authors find with adequate chin and angle projection, this may not be necessary.

Conclusion:

Male non-surgical rejuvenation is a growing segment of the aesthetic industry. Differences exist in the anatomy and aging process between males and females. Understanding these differences is important in treatment planning and execution for male aesthetic procedures.

References:

1. Optimizing Male Periorbital Rejuvenation.

Scheuer JF 3rd, Matarasso A, Rohrich RJ. Dermatol Surg. 2017 Nov;43 Suppl 2:S196-S202. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001344.

2. Volumetric Structural Rejuvenation for the Male Face.

Sadick NS. Dermatol Clin. 2018 Jan;36(1):43-48. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.09.006.

3. Aging changes in the male face. Leong PL. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2008 Aug;16(3):277-9, v. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2008.03.007.

4. Injectables and fillers in male patients. Dhaliwal J, Friedman O. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2008 Aug;16(3):345-55, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2008.03.002.

5. Aging in the Male Face: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors. Keaney TC. Dermatol Surg. 2016 Jul;42(7):797-803. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000505.

6. The Male Aesthetic Patient: Facial Anatomy, Concepts of Attractiveness, and Treatment Patterns. Keaney TC, Anolik R, Braz A, Eidelman M, Eviatar JA, Green JB, Jones DH, Narurkar VA, Rossi AM, Gallagher CJ. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Jan 1;17(1):19-28.

7. BeautiPHIcation™: a global approach to facial beauty. Swift A, Remington K. Clin Plast Surg. 2011 Jul;38(3):347-77, v. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2011.03.012.

8. Injectable Filler Techniques for Facial Rejuvenation, Volumization, and Augmentation.

Bass LS.

Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015 Nov;23(4):479-88. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2015.07.004.

9. Current Concepts in Filler Injection. Moradi A, Watson J. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015 Nov;23(4):489-94. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2015.07.005.

2015 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. https://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/Stats2015.pdf